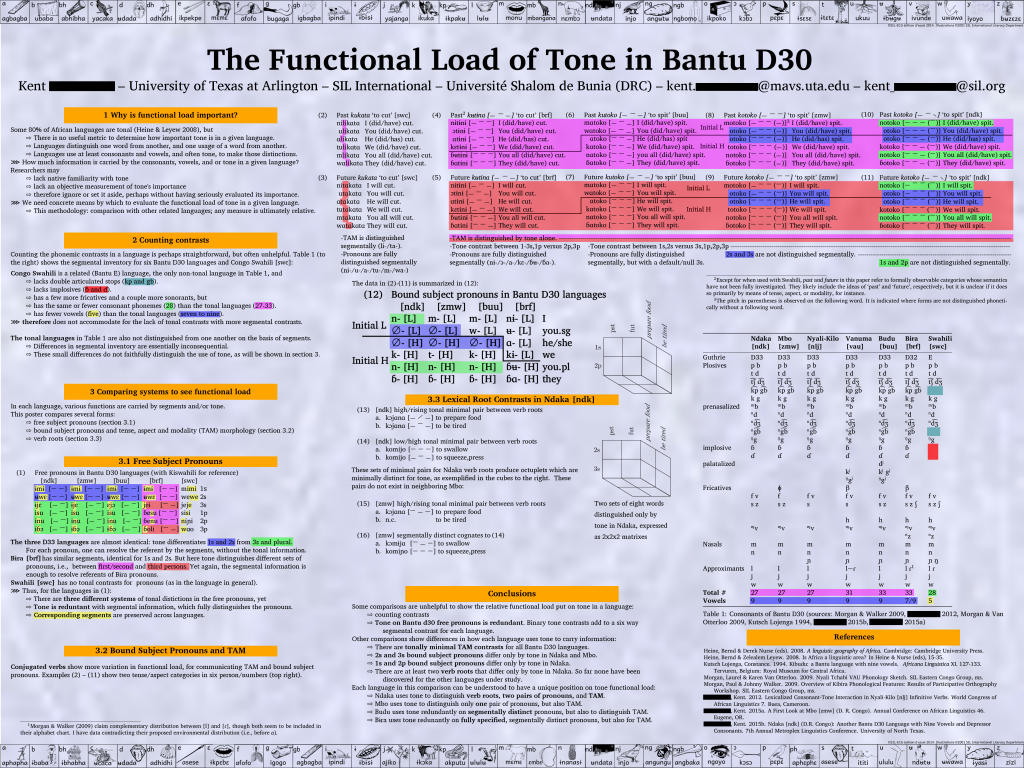

I presented a poster earlier this term at the Metroplex Linguistics Conference, a conference for linguists throughout the Dallas/Fort Worth area. This year it was sponsored by the Graduate Institute of Applied Linguistics (G.I.A.L.), where a lot of our colleagues either teach or get training before heading to the field. My poster was on the functional load of tone:

While much of that detail may not make much sense to you, the main point is that tone is important for conveying meaning in tonal languages, but not necessarily to the same extent, or in the same ways, from one language to another. So this poster took four of the (tonal) languages that I’m working on, and compared them to each other, alongside Swahili, a non-tonal language used to communicate between people groups where these languages are spoken.

One thing that I found out that was interesting was that the importance of tone in a given language can’t be determined by the number of consonants or vowels in the languages. Each of these languages have about the same consonants (27-33) and vowels (7-9), but they use tone in very different ways. This can be seen in the conjugation of verbs, where subjects, for example, are indicated by consonants, vowels, and tone in each of these languages (this is like the ‘s’ in ‘He walks‘, which is not there in ‘I walk’) . But in some of these languages, the consonants and vowels are enough to tell who is doing the action, so at least that part of the writing system could work without writing the tone. In one of those languages (Bɨra), there are letters for each kind of subject. For the other (Bʉdʉ), one of the subjects has no consonant or vowels (like the agreement on ‘I walk_’), but it is still clear who is doing the action, since there is only one such subject. But in the other two languages, there are two subject pronouns that have no consonants or vowels, so you can only tell them apart with tones. And in one of those languages (Ndaka), there is another pair of pronouns, which are both ‘n-‘ , so they are also distinguished only by tone.

So each language puts progressively more importance on tone; it becomes harder and harder to convey all the language’s meaning without indicating tone. In addition to the above, Ndaka also has verb root minimal pairs. For instance, the difference between ‘cook’ and ‘become tired’ is only in the tone; they have the same consonants and vowels. That leads to the following set of eight words, at least six of which are distinguished by tone:

- ɔjana. [˨˨˨˨ ˨˧˦ ˧˨˩] You were tired.

- ɔjana. [˦˦˦˦ ˦˦˦˦ ˨˨˨˨] He/she/it was tired.

- ɔjana. [˨˨˨˨ ˦˦˦˦ ˦˦˦˦] You will be tired.

- ɔjana. [˦˦˦˦ ˦˦˦˦ ˦˦˦˦] He/she/it will be tired.

- ɔjana. [˨˨˨˨ ˨˧˦ ˧˨˩] You prepared food.

- ɔjana. [˦˦˦˦ ˦˦˦˦ ˨˨˨˨] He/she/it prepared food.

- ɔjana. [˨˨˨˨ ˨˨˨˨ ˦˦˦˦] You will prepare food.

- ɔjana. [˥˥˥˥ ˨˨˨˨ ˦˦˦˦] He/she/it will prepare food.

If you want to pronounce these, in the International Phonetic Alphabet j is pronounced like ‘y’ in ‘you’, so these might be pronounced something like “oh-yawn-ah”, though with different pitches, [˥˥˥˥] being higher and [˨˨˨˨] being lower.

One of the things I’m doing now is developing this material into a presentation for the Annual Conference of African Linguistics (ACAL) next spring. And that will further develop my analysis of the tone in these languages, which will form the majority of my dissertation.

0 Comments