For those of you that have followed my analysis of sound systems in (so far) unwritten languages, I’m sure you’ve already heard enough about tone and vowels. So today, I thought I’d write about consonants!

Language sound systems generally store information in three places. We know consonants (with obstructed airflow) and vowels (with shaped, but not obstructed airflow) from English, but probably about half the world’s languages also use tone (and some estimate 80% of those in Africa). Other languages (which are more like English) use contrastive stress, meaning that the stress on a word changes not only the pronunciation, but the meaning. If I say emPHAsis instead of EMphasis, you get what I mean, though it sounds wrong. But CONvert and conVERT are two different words, the first being a noun, and the second being a verb. We don’t do this kind of thing much, but this is just one of the several ways languages communicate the difference between one word and another.

So you know that tone is like stress (though more complicated, and used a lot in Africa, but not really in English). And you know about ATR, which gives some African languages interesting vowel harmony patterns (and more vowels than Spanish, but less than English). But what about consonants? You might think that I don’t work with consonants much, since I’m studying tone, but that’s just not so. First of all, almost every word has consonants, so they can’t be avoided.

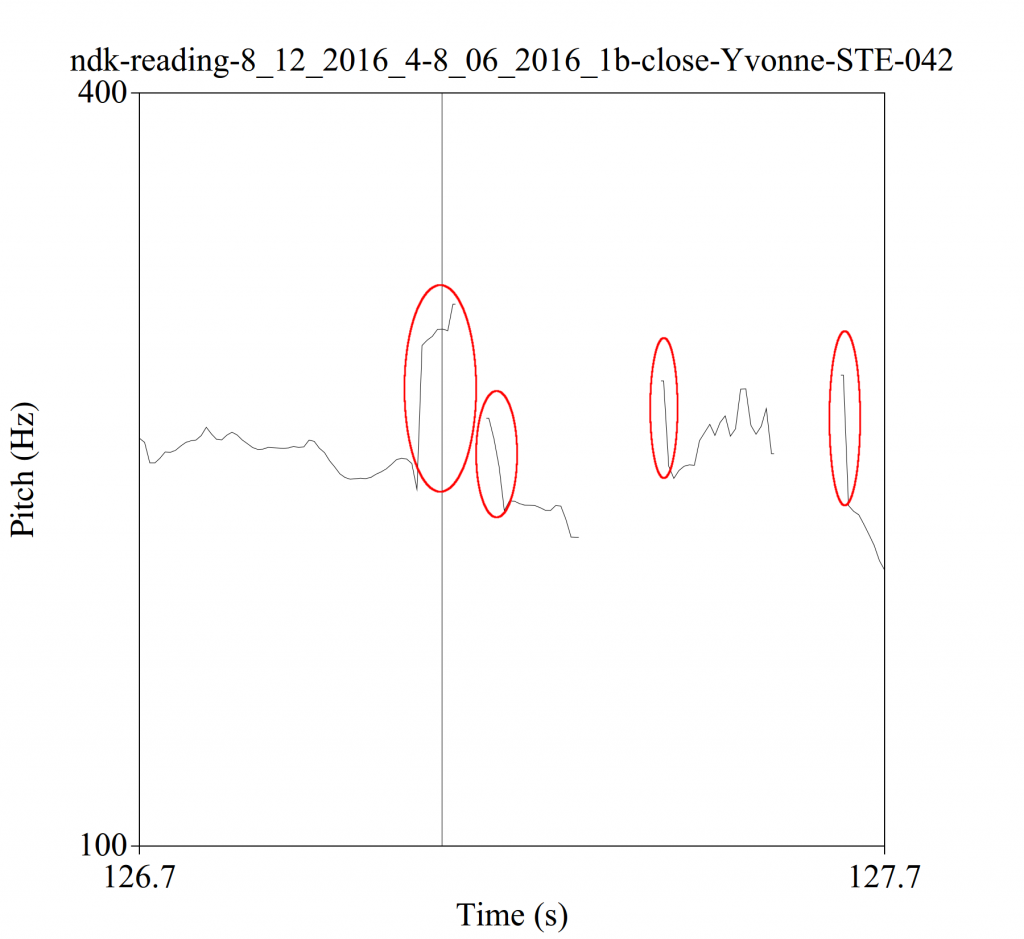

Secondly, and slightly more importantly, there are slight and meaningless (i.e., not changing word meaning) but potentially distracting changes to pitch made by consonants, as in the spikes circled in the following picture:

It would be easy to look that those quick jumps and drops in pitch, and say “wow, something’s going on there”. But there isn’t. These are just a result of the vocal folds starting and stopping vibrating as they go between vowels (with vocal fold vibration) and voiceless consonants (where the vocal folds are relaxed). So as I look at pitch traces with these effects, its important to understand what they are, and to abstract them away, rather than pay much attention to them.

There is a third reason, which is more important to my research. Not only do I work with tone, but the languages I’m working on now have what we call Consonant-Tone Interaction. That is, the tone of these languages is actually impacted by the consonants around them. So it’s important to understand what consonants are in each word.

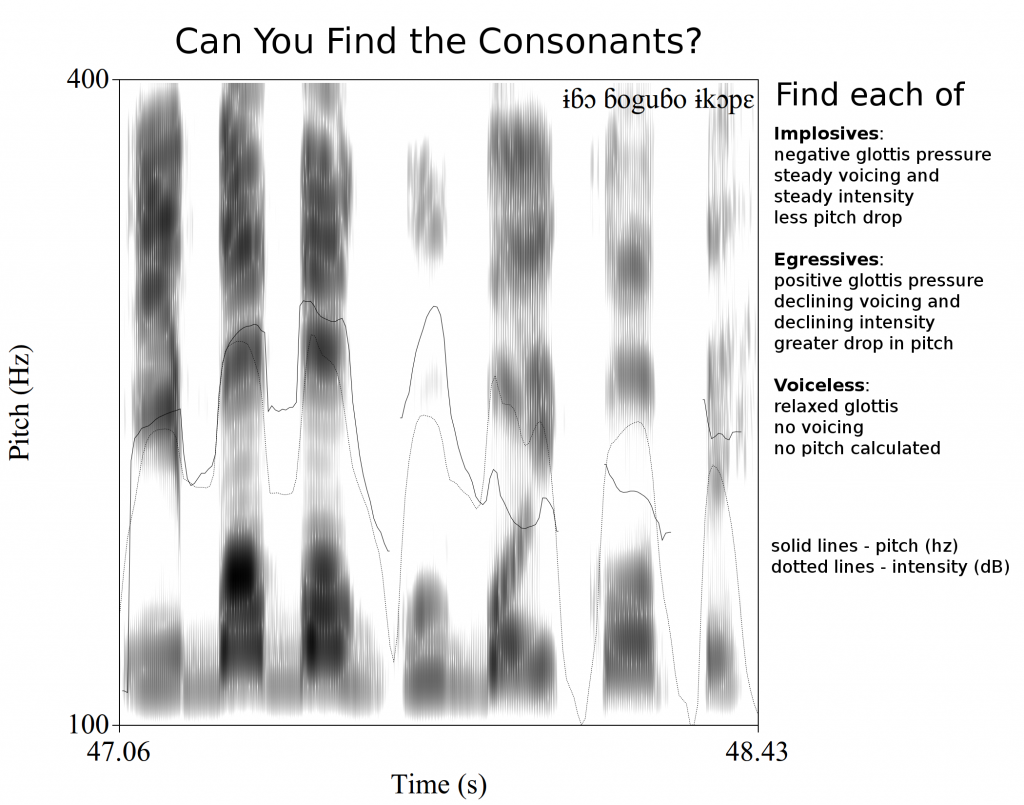

Normal consonants (in these languages) have a slight negative pressure (sucking) before release, and these consonants don’t impact tone. But those where the airstream is more like typical English pronunciation are less common, but they impact the tone. So how do we tell the difference? There are many ways, but one I’d like to show you can be seen in the following picture:

I originally developed this image as an exercise, so rather than just go and give you the answer, I’ll pose the question, and you can submit answers in the comments. 😉

I’ll help you out with a few points:

- The three categories are named and described in the key on the right

- The vowels are the dark vertical bands; the consonants are between those. 🙂

- Most of the vertical space for consonants is blank/white, but there is a small dark band at the bottom for some, which indicates voicing.

- If you look at pitch, recall that tone is relative pitch, so compare the drop over a consonant to the pitches over the vowels on each side, which may not be the same.

So, which consonant types can you find? How many of each, and in what order?

0 Comments